Millions of Americans are now working remotely or from home due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Many don’t know when or if they will return to the office as usual. If you or any of your employees are among this legion of remote workers, there are some especially important tax tips to be aware of.

Multi-State Taxation

Folks who have worked from another state that isn’t their usual place of business, may need to file returns and pay taxes to more than one state for 2020. Nearly all states that have income taxes impose them on workers who are just passing through. In two dozen states, that can be for just a single day.

This requirement may come as an unpleasant surprise to you or your employees at tax time if you don’t understand the rules. In fact, according to a story in the Wall Street Journal, more than 70% of Americans aren’t aware that telecommuting from another state can affect a worker’s state-tax bill.

This issue gets a bit complex when you consider the fact that each state’s tax system plays by different rules. When a business owner or employee owes income tax to more than one state, the various state systems often clash, and you as a taxpayer can wind up owing more tax than you expect. This year some states have made this issue even more complicated by issuing special tax rules just for the pandemic.

Basically, if you’re earning money in a state where you’re not a resident, you could be required to file a non-resident tax return there, as well as pay taxes.

A Patchwork of State Tax Rules

Different states have different rules for when you need to file a tax return. Fourteen states and the District of Columbia have announced they won’t tax people working there remotely because of COVID-19, according to data compiled by the American Institute of CPAs (AICPA).

Other states have reciprocity agreements with their neighbors to avoid taxing workers’ income twice. They offer their citizens a tax credit to offset the income taxes their workers’ pay in a different state. Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, and Washington D.C., for instance, have such agreement in place, as do Pennsylvania and New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut.

Unfortunately, other states are not as generous. States including Massachusetts, Maine, Georgia, and Pennsylvania intend to tax remote workers whose jobs are based in-state while they are working remotely out of state due to the pandemic, according to the AICPA.

A group of seven states follow the “convenience of the employer” rule, which taxes telecommuters based on where their employer’s office is located, according to the Tax Foundation. Those states include Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, Nebraska, New York, and Pennsylvania. Under these rules, an employee is treated as if they work in their employer’s home state even if their work is performed elsewhere for what is termed the “convenience of the employer.”

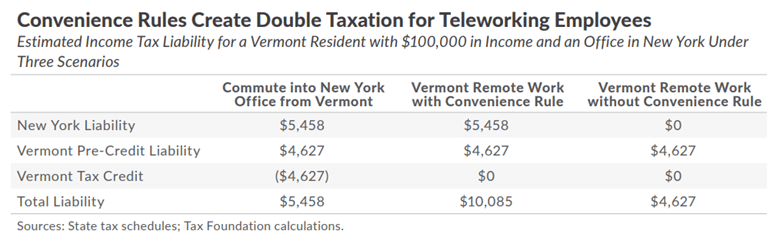

As an example, what if a customer service worker lives in Vermont but commutes to the employer’s phone center in New York? When that work is physically performed in New York, everything operates normally: New York taxes the worker’s income and so does Vermont, but Vermont offsets the tax liability with a credit for taxes paid on income earned in New York.

Beware Double Taxation

But what if the New York phone center closed due to the pandemic and the customer service worker is now fielding calls at home in Vermont?

But what if the New York phone center closed due to the pandemic and the customer service worker is now fielding calls at home in Vermont?

If that work is now being performed in Vermont, then Vermont no longer regards the work as being performed in New York — for the obvious reason that it is not. Meaning, no credit from the worker’s home state of Vermont. That means both states’ full income taxes apply. Double taxation.

Steps to Take Now to Lower Your Tax Bill

Considering these multi-state taxation complexities, remote workers who don’t understand the rules risk paying higher tax bills and perhaps interest and penalties. But to avoid this, here are steps to take right now.

First, determine where you were in 2020. How many states did you work in? How many workdays did you spend in each state? State taxes depend in part on whether you’re a resident, and that can depend on how many days you were in the state. How will a state know you worked there?

There is a paper trail. Employers will include this information on W-2 forms which you must submit with your tax return.

Second, find out the rules for the states where you worked:

- What are the criteria for being a taxable resident of the state you worked in vs. the state you lived in?

- Are there special pandemic rules that make them different this year?

- Does the state you worked from have an agreement with the state where your office is located that prevents double taxation? These are common in states that share a border.

For information, check state-tax websites or this chart from the AICPA. Also check the taxes on non-residents if you worked in a state but not long enough to be a resident there. Most states have these rules.

Third, find out the tax rates and rules in the states where you worked. If you’ll owe taxes in two or more states, are there any credits to prevent or reduce double taxation?

Talk to your employer. State tax authorities can be aggressive, but they may desist if your employer has assigned you to an existing office in another state and then withheld taxes for that state.

For example, let’s say you worked for a New York-based national firm, but moved to your Florida vacation home during the pandemic. If your firm reassigned you to a nearby Florida office and has adjusted your W-2 form to show this, then you stand a better chance of avoiding New York state income taxes.

“Domicile” also counts. State tax law often considers where the worker’s true home is in addition to time spent in-state. Key factors include where someone votes, has club or religious affiliations, and has a driver’s license. High-tax states like California and New York can claim that high income earners who left during the pandemic and later return owe 2020 tax because they didn’t change their domicile.

Fourth, adjust your state withholding or estimated taxes. If you suspect you’ll owe more tax than you anticipated, consider upping your withholding or making larger estimated tax payments. Remember, paying in too little during the year can trigger interest and penalties at filing time.

Finally, get professional help. If you believe you may have a large tax liability, say due to a big bonus you received, or from selling a key investment while working remotely out-of-state this year, contact TSP Family Office right away to learn about smart, and potentially tax-saving, moves you can make. It could save you a bundle at tax time.